Hygroscopic Swelling

Solids can absorb water molecules in a humid environment, and this accumulation can cause the solid to swell and result in increased stress and strain [1]. This phenomenon happens in several environments, like industrial plants, naval applications and biological laboratories, and it must be modeled accurately to investigate its effects.

This swelling results in an inelastic strain ![]() that is proportional to the difference between a concentration and a strain-free reference configuration:

that is proportional to the difference between a concentration and a strain-free reference configuration:

Here ![]() represents the coefficient of hygroscopic swelling,

represents the coefficient of hygroscopic swelling, ![]() is the moisture concentration and

is the moisture concentration and ![]() a moisture referencing value. The moisture concentration is typically described in [

a moisture referencing value. The moisture concentration is typically described in [![]() ] and governed by the mass transport equation.

] and governed by the mass transport equation.

The water molecules' absorption leads to two different types of effects on the solids, depending on the constraints. On free structures, it induces deformations, while on completely fixed structures, it induces stresses. In real structures, generally only partially constrained, it leads to a mixture of effects.

This application example shows a model of hygroscopic swelling combined with thermal expansion.

Hyperelastic Material and Multiphysics

As introduced in the Hyperelasticity monograph, it is possible to couple several phenomena within a finite elasticity deformation process through a kinematic decomposition. The moisture-induced stress can be modeled similarly to the thermoelastic deformative process, and it is then possible also to couple both the effects.

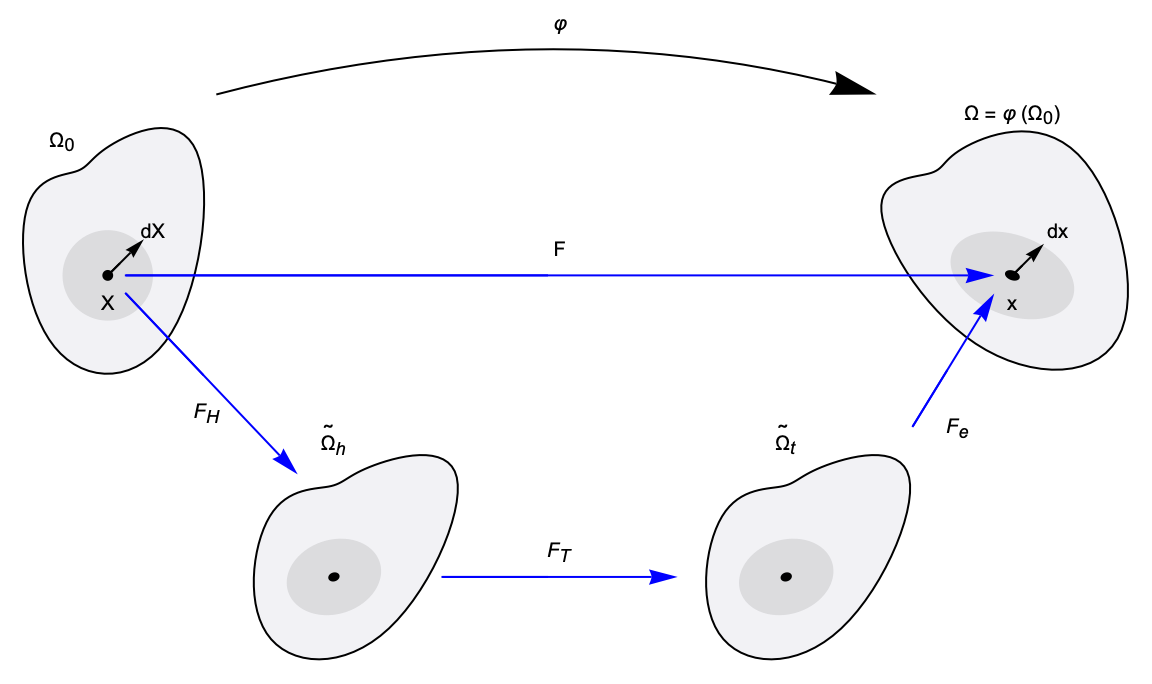

The kinematic approach starts by splitting the deformation gradient into an elastic part ![]() and an inelastic part

and an inelastic part ![]() :

:

where ![]() contains both the inelastic contributions. That is the contriutions due to the thermal inelastic deformation gradient

contains both the inelastic contributions. That is the contriutions due to the thermal inelastic deformation gradient ![]() and to the hygroscopic inelastic deformation gradient

and to the hygroscopic inelastic deformation gradient ![]() .

.

The thermal inelastic deformation gradient is introduced in the thermoelasticity section as:

For the definition, either the built-in thermal strain function can be used or, alternatively, the thermal inelastic deformation gradient can be used.

The hygroscopic deformation gradient is referred to the moisture relative concentration through the coefficient of hygroscopic swelling as:

A small helper function is written to compute the hygroscopic strain.

So the total deformation gradient ![]() maps the reference configuration

maps the reference configuration ![]() to the current configuration

to the current configuration ![]() . However, for each intermediate configuration, different phenomena are described. The current configuration includes the mechanical problems described, focusing on the elastic deformation gradient, defined as:

. However, for each intermediate configuration, different phenomena are described. The current configuration includes the mechanical problems described, focusing on the elastic deformation gradient, defined as:

To set up the equilibrium equation, the elastic Piola–Kirchhoff stress ![]() needs to be pulled back to the reference configuration, to get a first Piola–Kirchhoff stress

needs to be pulled back to the reference configuration, to get a first Piola–Kirchhoff stress ![]() , accounting also for the inelastic contribution [3]. For more information, see the Hyperelasticity monograph.

, accounting also for the inelastic contribution [3]. For more information, see the Hyperelasticity monograph.

The total deformation gradient ![]() maps the reference configuration

maps the reference configuration ![]() to the current configuration

to the current configuration ![]() . With a decomposition, two intermediate configurations are introduced. The hygroscopic inelastic deformation gradient

. With a decomposition, two intermediate configurations are introduced. The hygroscopic inelastic deformation gradient ![]() maps

maps ![]() to

to ![]() , while the thermal inelastic deformation gradient maps

, while the thermal inelastic deformation gradient maps ![]() to

to ![]() . In the end, the elastic deformation gradient

. In the end, the elastic deformation gradient ![]() maps

maps ![]() to

to ![]() .

.

Both the thermal and diffusive phenomena are described in their configuration. The mass transport phenomenon is represented in the ![]() intermediate configuration with the diffusion equation, while the thermal process is represented in the

intermediate configuration with the diffusion equation, while the thermal process is represented in the ![]() configuration with the heat equation described in the following.

configuration with the heat equation described in the following.

In addition, pull-back operations are needed to map the thermal and diffusive components to the reference configuration in order to solve the fully coupled PDE in the reference configuration.

The hygroscopic inelastic deformation gradient maps the reference configuration ![]() into the first intermediate configuration

into the first intermediate configuration ![]() , where the mass diffusion phenomenon is described. The stationary diffusion equation in the solid domain reads:

, where the mass diffusion phenomenon is described. The stationary diffusion equation in the solid domain reads:

where ![]() represents the moisture concentration,

represents the moisture concentration, ![]() is the diffusion coefficient, and

is the diffusion coefficient, and ![]() denotes a mass production or consumption rate. For more information about the diffusion equation, see the Mass Transport monograph.

denotes a mass production or consumption rate. For more information about the diffusion equation, see the Mass Transport monograph.

In order to be solved together with the other PDE sets, the diffusion equation needs to be pulled back to the reference configuration, such that it is in the same reference frame. This requires us to pull back both the divergence and the gradient operators [2, p. 521], leading to:

where ![]() is the hygroscopic inelastic deformation gradient and

is the hygroscopic inelastic deformation gradient and ![]() . As mentioned in the Hyperelasticity monograph for the thermo-elastic coupling, the Jacobian is in front of the divergence, which makes this equation not suitable for the finite element solver. More details are given in the section on The Coefficient Form of a PDE.

. As mentioned in the Hyperelasticity monograph for the thermo-elastic coupling, the Jacobian is in front of the divergence, which makes this equation not suitable for the finite element solver. More details are given in the section on The Coefficient Form of a PDE. ![]() needs to be pulled inside the divergence, and this can be done by adding a further term that compensates the effect that

needs to be pulled inside the divergence, and this can be done by adding a further term that compensates the effect that ![]() has inside the divergence:

has inside the divergence:

This is in a proper coefficient form, and the equation to implement is:

Similarly, the heat equation also needs to be pulled back. This is described in the Hyperelasticity monograph and follows the same pull-back operation, with the only difference being that the deformation gradient, which leads to the second intermediate configuration, is no longer only the thermal inelastic one, but the complete inelastic deformation gradient, including both the thermal and hygroscopic ones, as described in Eqn. (1).

So the proper coefficient form and the equation to implement is:

In the following, an example is implemented to show the application of the coupling of the mechanical, thermal and moisture diffusion phenomena:

Gasket Application Example

Polymeric rubbers play a crucial role in the modern industrial landscape. These materials find applications across a wide range of sectors, thanks to their unique properties, such as resilience, high deformability and elastic response, resistance to chemicals and ease of production. However, some of these materials may not respond so well to thermal load and/or a humid environment.

In the following example, a gasket made from a rubber-like material is shown. The gasket fills a space in between two plates, and it is used in an industrial oven working with mid-range temperature and a high moisture concentration. The plates are made of hydrophobic material that maintains a very low local moisture concentration. In addition, the plates are subjected to different temperatures. The upper one is also subjected to a vertical load, which leads to a large deformation compared to the size of the gasket.

In addition to the main mechanical load, the material is subject to a humid environment with different temperature ranges. Plates at different temperatures may induce a thermal deformation, which can increase stress and strain. In addition, due to construction reasons of the system, the internal region is filled with air with a very high moisture content, which may affect the hygroscopic deformation of the material.

A gasket made in from a rubber-like material shown in gray is subjected to vertical load ![]() . A cold plate

. A cold plate ![]() , shown in blue, fixes the bottom side, while the upper portion is loaded with a hot plate

, shown in blue, fixes the bottom side, while the upper portion is loaded with a hot plate ![]() , shown in brown, representing both a mechanical load and a temperature boundary condition. The internal region

, shown in brown, representing both a mechanical load and a temperature boundary condition. The internal region ![]() is filled with air very rich in moisture, representing a moisture boundary condition shown in pink. Due to symmetry, the problem may be described representing only half the domain.

is filled with air very rich in moisture, representing a moisture boundary condition shown in pink. Due to symmetry, the problem may be described representing only half the domain.

Domain

The domain is symmetric, and it is sufficient to model half the domain. To represent the mechanical symmetry condition, the horizontal displacement of the midplane is fixed at ![]() , while the vertical displacement is left free to move.

, while the vertical displacement is left free to move.

The bottom plate represents both a thermal and a mechanical boundary condition. It represents a cold temperature and fixes the vertical displacement of the rubber, while a horizontal slide is allowed. In contrast, the upper plate represents a hot surface with a mechanical load. In addition to that, this plate is strongly glued with the gasket, linking their displacements. For this reason, the plate is also represented, described as a much stiffer material compared to the rubber-like one.

The plate, due to construction requirements, is made of a hydrophobic material with a near-zero concentration in moisture, while the internal boundary, shown in pink, has a very high moisture concentration ![]() .

.

Due to the different phenomena involved, the PDEs are expressed as a function of displacements, temperature and concentration, all depending on spatial position.

The geometrical domain is represented by 11 boundary lines that connect 10 vertexes. Two different domains are identified by region markers, one for the deformable rubber and one for the stiffer plate. The generation and usage of ElementMarker is explained in the ElementMesh generation tutorial.

Material Properties

Next, material properties are defined. The material mechanics is described as a nearly incompressible neo-Hookean hyperelastic behavior.

Mass Transport

Before looking at the fully coupled PDE, it is instructive to take a look at the hygroscopic absorption and how that can affect the mechanics, and thus how to couple the physics.

As mentioned before, the dependent variable in the mass balance equation is the species concentration ![]() , which varies with position

, which varies with position ![]() . The partial differential equation (PDE) model describes how chemical species are transported in a solid medium. First of all, an investigation of the diffusive process is performed.

. The partial differential equation (PDE) model describes how chemical species are transported in a solid medium. First of all, an investigation of the diffusive process is performed.

Due to the hydrophobic boundary condition on the plates and to the internal elevated concentration, the moisture spreads through the material thickness towards the right side.

In summary, by coupling the moisture diffusion with the induced strain in the mechanical model, a relatively high expansion can be expected on the internal side and less relevant effects near the plates.

Multiphysics

In order to investigate the effect of the moisture inside the material, a fully coupled hygro-thermo-mechanical problem is shown next. First, the different phenomena are described and then the three coupled PDEs are solved together with a parametric solver, allowing for gradually increasing the boundary conditions through a load multiplier ![]() .

.

Diffusion

The diffusion problem was described in the previous section; however, the pull-back operation needs to be included to fully couple the phenomena. The internal boundary conditions are replaced, introducing the load multiplier.

As introduced in Eqn. (2), the diffusion equation is written including the pull-back operation and a compensation term.

Solid mechanics

In the mechanical description, the equation representing the displacement ![]() and

and ![]() is introduced.

is introduced.

The mechanical description includes the vertical displacement constraint on the bottom side, the horizontal displacement constraint on the symmetry side and the vertical load on the upper plate. A nearly incompressible neo-Hookean material model is used, and the plate is represented as a very stiff material, with a material coefficient four orders of magnitude larger than that of the deformable rubber.

Thermal

The heat equation describing the temperature ![]() is then introduced as expressed in Eqn. (3), including the pull-back operation and the compensation term. The boundary conditions on temperature are applied through the load multiplier

is then introduced as expressed in Eqn. (3), including the pull-back operation and the compensation term. The boundary conditions on temperature are applied through the load multiplier ![]() .

.

Solution

The final, coupled PDE involves the mechanical, the thermal and the diffusion components, and so the solutions vector contains both the displacements u[x,y] and v[x,y], the temperature ![]() field and the concentration

field and the concentration ![]() field.

field.

Now, the parametric solver is set up. All the boundary load values are connected to the multiplier parameter ![]() .

.

Sometimes, it is needed to help NDSolve figure out the ordering of the dependent variables. This is explained in more detail in the Finite Element Best Practice documentation.

The parametric function allows us to, step by step, slowly increase the multiplier ![]() from 0 to 1, thus increasing the vertical force, the heat exchanges and the moisture concentration at the boundaries.

from 0 to 1, thus increasing the vertical force, the heat exchanges and the moisture concentration at the boundaries.

Post-processing

After obtaining the solutions, it is interesting to investigate how the different involved phenomena affect stress and strain in the material.

The Green–Lagrange strain tensor ![]() represents the total strain. The total Cauchy–Green strain tensor

represents the total strain. The total Cauchy–Green strain tensor ![]() contains, due to the multiplicative decomposition, the contributions of both the inelastic and elastic deformation processes.

contains, due to the multiplicative decomposition, the contributions of both the inelastic and elastic deformation processes.

The expression of the total Green–Lagrange strain tensor ![]() is given by:

is given by:

Each Cauchy–Green strain tensor is computed starting from the corresponding deformation gradient, and then the Green–Lagrange strain tensor is computed as indicated in the Hyperelasticity monograph.

Next, the thermal strain ![]() needs to be computed. The inelastic thermal deformation gradient is defined as a function of the temperature

needs to be computed. The inelastic thermal deformation gradient is defined as a function of the temperature ![]() and the load multiplier

and the load multiplier ![]() . These need to be replaced with the actual values. Since the material is isotropic, it is sufficient to consider any one of the diagonal components of the thermal strain, as all diagonal components are the same.

. These need to be replaced with the actual values. Since the material is isotropic, it is sufficient to consider any one of the diagonal components of the thermal strain, as all diagonal components are the same.

It is possible to replace the temperature results over both the undeformed or deformed mesh, but the plot domain needs to be selected accordingly. For the deformedTemperature, the plot needs to be done over the deformedMesh.

It is possible to use the same approach for the hygroscopic strain computation.

The hygroscopic strain ![]() can be computed, replacing the moisture concentration

can be computed, replacing the moisture concentration ![]() and the load multiplier

and the load multiplier ![]() . Since the material is isotropic, it is sufficient to consider any one of the diagonal components of the thermal strain, as all diagonal components are the same.

. Since the material is isotropic, it is sufficient to consider any one of the diagonal components of the thermal strain, as all diagonal components are the same.

Then it is possible to compute the elastic Cauchy–Green by inverting Eqn. (4), where the inelastic Cauchy–Green contains both the thermal and the hygroscopic contributions.

To compute the total Cauchy-Green strain tensor ![]() ,

, ![]() is solved for

is solved for ![]() :

:

As a last step, it remains to compute the distribution of stresses inside the material caused by the overall deformation.

The multiplier ![]() , the temperature

, the temperature ![]() and the moisture concentration

and the moisture concentration ![]() are replaced such that the each component is a simple interpolating function that can be evaluated.

are replaced such that the each component is a simple interpolating function that can be evaluated.

References

1. Weitsman, Y. J. "Effects of Fluids on Polymeric Composites," Comprehensive Composite Materials. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-042993-9/00068-1.

2. Yosibash, Z. Weiss, D. and Hartmann, S. (2014). "High-Order FEMs for Thermo-hyperelasticity at Finite Strains. Computers and Mathematics with Applications, Vol. 67, pp. 477–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.camwa.2013.11.003

3. Wriggers, P. Nonlinear Finite Element Methods, Springer, 2008.