Hyperelastic Model Comparison

| Introduction | FEM Uniaxial Test |

| Uniaxial Test Data Generation | Conclusion |

| Model Fitting | Nomenclature |

| Analytical Comparison | References |

The following examples compare different hyperelastic models, with a brief discussion about picking the model that best fits your experimental data.

Introduction

Selecting the correct hyperelastic model for a specific material requires considering several factors, including the material's mechanical behavior, available experimental data and the intended application.

Experimental data is crucial for selecting an appropriate hyperelastic model. Mechanical tests, such as uniaxial tension, compression or shear tests, are conducted to measure the material's stress-strain response under different loading conditions.

For soft tissue, for example, uniaxial tensile testing is commonly used to gain experimental data, due to the relatively simple and controlled experimental setup. The specimens are subjected to controlled tensile forces in a single direction, allowing for precise measurements and analysis. The uniaxial loading condition ensures that the stress and strain are predominantly applied along one axis, simplifying the analysis of the mechanical behavior. Displacement data is recorded as a function of force between the grips of the testing machine.

More information on experimental tests is given in the Hyperelasticity monograph.

The finite element context is loaded for additional functions used in the remainder of the tutorial.

Uniaxial Test Data Generation

In order to fit the hyperelastic model of interest, experimental data is needed to describe the material behavior aforementioned. In the following section, a uniaxial tensile test is considered to collect data representing the stress-stretch relation. To avoid having to go to the lab, the experimental data is generated virtually. For this, an analytical expression is considered, relating stress and stretch due to a specific constitutive behavior.

As expressed in the Hyperelasticity monograph, the uniaxial stress is related to the strain energy ![]() and the stretch

and the stretch ![]() as:

as:

To generate virtual experimental data, a constitutive model needs to be selected. For instance, a Yeoh model is used, which has the simplicity of a polynomial function while still showing a well marked nonlinear behavior. Clearly, a different constitutive model or different material parameters change the experimental data and consequently, all the following comparison results.

The process starts by inserting the Yeoh strain energy into the uniaxial stress expression and gives:

where ![]() is the first strain invariant

is the first strain invariant ![]() .

.

Due to the incompressibility constraint ![]() , the second and third principal stretches are related to the main principal stretch as

, the second and third principal stretches are related to the main principal stretch as ![]() . The first strain invariant can then be expressed with respect to the main stretch

. The first strain invariant can then be expressed with respect to the main stretch ![]() as:

as:

In the following, experimental data is generated as a stress-stretch relation with the addition of noise to simulate the imperfection of real data. The noise added also shows how the performed material model fitting can be affected by data quality.

It is important to realize that in this example, two different data ranges data are considered. The data from the experiment is typically over a larger range than the data used for the actual model fit. This approach ensures the creation of the most accurate fit possible by restricting the fitting process to the data range of interest without extending beyond it.

Although the virtual experimental data reaches a maximal stretch of ![]() , the fitting of the models is performed on a restricted range. This is to show later how models' accuracy depends on the chosen data range. In fact, as it will be shown later, models that perform similarly within a certain range can exhibit large differences when applied outside of this range.

, the fitting of the models is performed on a restricted range. This is to show later how models' accuracy depends on the chosen data range. In fact, as it will be shown later, models that perform similarly within a certain range can exhibit large differences when applied outside of this range.

To emphasize this once more, the choice of the maximal stretch used for the model fitting here is arbitrary. When performing a fit with real data, one should take into consideration the expected stretch in the actual application and choose the data range based on that.

Model Fitting

In the following step, a hyperelastic material model fit is created based on the uniaxial tensile test data. Typically, the data is obtained from a series of experiments, or in our case, virtual material data has been created. In this section, several incompressible hyperelastic material models are fitted to the same data.

Considering the strain energy ![]() of a specific model leads to an analytical expression from which it is possible to identify the material parameters for the desired constitutive model through a fitting procedure.

of a specific model leads to an analytical expression from which it is possible to identify the material parameters for the desired constitutive model through a fitting procedure.

For each model, the material parameter identification procedure is the same: First, the strain energy is derived with respect to the first and second invariants to compute the uniaxial stress ![]() , as expressed in Eqn. (1). Then, a numerical fitting is performed to search for the optimal material parameters to represent the test data.

, as expressed in Eqn. (1). Then, a numerical fitting is performed to search for the optimal material parameters to represent the test data.

Neo-Hookean

The strain energy for the incompressible neo-Hookean model is:

For the uniaxial test, the stress from Eqn. (2) reads:

Mooney–Rivlin Two Parameters

The strain energy for the incompressible two-parameters Mooney–Rivlin model is:

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the two material parameters.

are the two material parameters.

A consistent fitting also requires an additional constraint, ![]() , in order to satisfy the positiveness of the strain energy. The constraint ensures numerical material stability.

, in order to satisfy the positiveness of the strain energy. The constraint ensures numerical material stability.

For the uniaxial test, the stress from Eqn. (3) reads:

Mooney–Rivlin Five Parameters

The strain energy for the incompressible five-parameters Mooney–Rivlin model is:

So for the uniaxial test, the stress from Eqn. (4) reads:

Mooney–Rivlin Nine Parameters

The strain energy for the incompressible nine-parameters Mooney–Rivlin model is:

For the uniaxial test, the stress from Eqn. (5) reads:

Arruda–Boyce

The strain energy for the incompressible Arruda–Boyce model is:

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the two material parameters of the model, while the

are the two material parameters of the model, while the ![]() are the numerical coefficients from the Taylor expansion:

are the numerical coefficients from the Taylor expansion:

For the uniaxial test, the stress from Eqn. (6) reads:

Gent

The strain energy for the incompressible Gent model is:

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the two material coefficients.

are the two material coefficients.

For the uniaxial test, the stress from Eqn. (7) reads:

Yeoh

The strain energy for the incompressible Yeoh model is:

For the uniaxial test, the stress from Eqn. (8) reads:

Analytical Comparison

The following section compares the different fitted models. By focusing on the fitting range, the Yeoh, Mooney–Rivlin Five and Mooney–Rivlin Nine appear to best fit the available data due to their polynomial nature. In contrast, the simple Mooney–Rivlin, Arruda–Boyce and Gent appear to be reduced to linear-like behavior much like the neo-Hookean model.

The model behavior is strictly confined to the fitting range. When using the models beyond a stretch of ![]() , the majority of the models will diverge from the remaining experimental data, while the Mooney–Rivlin Five and the Yeoh model remain close to the expected range of stress. The models have been specially fitted to only a small part of the data,

, the majority of the models will diverge from the remaining experimental data, while the Mooney–Rivlin Five and the Yeoh model remain close to the expected range of stress. The models have been specially fitted to only a small part of the data, ![]() , to showcase their behavior beyond that stretch and to make a point to be careful to not use a model beyond its validity, which is given by the fitting range. A fit over the entire data range would lead to different results.

, to showcase their behavior beyond that stretch and to make a point to be careful to not use a model beyond its validity, which is given by the fitting range. A fit over the entire data range would lead to different results.

FEM Uniaxial Test

In the following section, several FEM analyses are implemented to show numerical difference between the models. The following analysis represents a uniaxial tensile test performed over a sample made of soft tissues showing a hyperelastic behaviour. The previously fitted model is used to describe the material.

3D Model

The uniaxial tensile test is a standardized procedure to mechanically test material. Here, a rectangular-shaped sample is pulled by one extremity. A full 3D model is initially shown in this section. In order to reduce computational complexity, a subsequent section will be implemented using a 2D model.

To generate a mesh for a geometry of this topological structure, where one dimension (thickness) is much smaller than the other ones, requires a large number of elements. This is mainly because of the necessity of having a sufficient number of elements in the smaller (thickness) layer, forcing the element size to be very small with respect to the structure size.

The reason to use at least three layers of elements in the thickness direction with solid elements is mainly due to two aspect: first, to accurately capture stress gradients in the thickness direction and secondly, to capture the geometrical behavior of the structure under tension. For a layer made up of a single element, a plane stress formulation might be better suited. Furthermore, the overall structure may have results stiffer than expected.

The specimen is deformed up to 120%. However, the right-hand side was not represented as a clamped boundary. Here the force is added on the boundary, and so it shows a highly deformed extremity.

To better represent the experimental procedure, the usage of a clamp, a different approach is used to model the clamped area. The clamping area of the specimen should remain in a nearly undeformed state because it is held fixed inside the clamp, which is what is pulled. To achieve that behavior, the material property of the specimen is adapted to be much stiffer in the area where the clamp is applied, as a model of the clamp. This addition will concentrate the deformation in the central side of the specimen, leading to more accurate results.

Also, three lines of elements should be used in the thickness to obtain accurate results, and this increases the model size. A first representation of the model could be obtained with a bidimensional representation.

Comparison in 2D

By reducing the problem to 2D, it is possible to rapidly compare several material models, showing their differences. Here, the 3D uniaxial tensile test from above is reproduced in 2D. One change is made by extending the domain to allow for a special area for the clamps that pull the specimen. Clamps are stiffer and their behavior is reproduced with a neo-Hookean material model that has a coefficient that is at least two orders of magnitude stiffer. This procedure allows the deformation of the extremity to be reduced and the analysis to be extended over the entire specimen.

Initially, the mesh is defined as well as boundary variables that will be used for all the material models application. Also several auxiliary functions are defined, so to define the same boundary problem, the corresponding parametric solver and the solution procedure for each different model are analyzed.

In the following, the same boundary conditions are used for all the simulations.

The following simulations allow several points of information to be extracted for each considered model. The stress-strain relation is sampled at the same steps of the parametric solution for each analysis.

The clamp regions are modeled as a high-stiffness neo-Hookean material in all simulations. This allows reducing the deformation on the extremities, focusing on the specimen strain.

Neo-Hookean

Due to the load directed along the ![]() direction and the specimen geometry, the most interesting strain effects are observable with the

direction and the specimen geometry, the most interesting strain effects are observable with the ![]() strain component referring to the deformation along the

strain component referring to the deformation along the ![]() direction. The same visible effect could be obtained by using the EquivalentStrain function.

direction. The same visible effect could be obtained by using the EquivalentStrain function.

Yeoh

Mooney–Rivlin two parameters

Mooney–Rivlin five parameters

Gent

Arruda–Boyce

Animation

Conclusion

The numerical results reveal several differences between the models. The most evident one appears comparing models inside and outside the fitting range. For instance, Gent and Mooney–Rivlin appear similar inside the fitting range but start to diverge outside, as well as the Mooney–Rivlin Five, Mooney–Rivlin Nine and Yeoh.

All hyperelastic models show nonlinearity; however, their intensity can vary depending on the model as well as on material parameters. Models like the neo-Hookean or Mooney–Rivlin, where the behavior is described almost as a straight line, clearly fit the experimental data in an averaged sense, but point by point, the differences are high, as shown with the analytical comparison. In such cases, the desired model should be fitted focusing not only on the experimental data range but also on the stress-strain ranges expected in the applications.

Another difference in behavior is shown in an initial stiffness of the specimen for the more linear models, like neo-Hookean, compared to more nonlinear models, like Yeoh. The material models have regions in which they are close to linear and other regions in which they are highly nonlinear. For example, for the Yeoh model, this is quite visible in the animation, where initially the deformation is larger then the neo-Hookean model deformation. Then, once a model approaches the highly nonlinear region, the deformation of the Yeoh will be less because of an increased stiffness in the model. The neo-Hookean model will display a larger deformation for the same stress.

This is also the reason why a force is applied as boundary condition and not a displacement one, as is typically done in the experimental procedure. Furthermore, such a boundary load allows different deformations of the specimen to be obtained between the different models. Then, differences in deformations are easier to understand thanks to their graphical appearance with respect to differences in stresses.

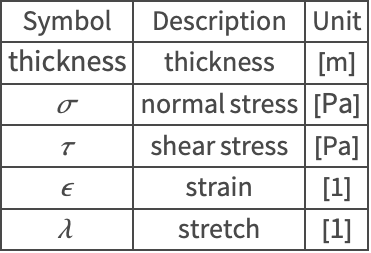

Nomenclature

References

1. A. Holzapfel, Nonlinear Solid Mechanics, Wiley, 2020. ISBN 978-0-471-82319-3.